Over the last 4 years I’ve often found myself in conversations with fellow engineers about our build and deployment process and how we feel it has become slower or is somehow causing more friction.

Eventually, as you live with a release process that you use every day you will find that you have these conversations relatively often. So how do you go about figuring out if you have issues and where they are.

TL;DR

- Draw it out

- Be mindful of your bias

- Measure everything

- Gather feedback on outliers

- Split and parallelize steps

- Look for human wait times

- Help your engineers solve their own problems earlier, before they become everyone else’s problem

Why measure

We all know that smaller releases, more often helps us deliver value to our customers, with less risk and this gives us a competitive advantage. Therefore we all want more throughput in our pipelines. If you have anything more complicated than a very simple one build, one test suite, one deploy pipeline then this can be a difficult thing to achieve.

We use a train metaphor for the pipelines involved in the shipping of our releases. Sure you can build more trains but that comes with complexity (to really drag the metaphor out, junctions and stations). A faster train is always going to bring benefits to your continuous delivery pipeline. Build faster trains.

To do this you need to measure how fast your releases are.

As an aside, I used to think that the number of releases performed per day is the best statistic to track. It is interesting but to be honest it’s basically bragging rights in a lot cases.

What you should care about is how fast you can release when you need to, not how many times you release per day/week/month

Optimize Wisely, Not With Bias

Most software engineers, me included, have their own bias about what they think is the worst, slowest, flakiest part of the release pipeline. This opinion comes not from observation and measurement but from scar tissue and technical preference. Resist the urge to optimize for what you think the problem is. Measure it and make informed decisions about where to spend your time.

What you will need

- A pen and paper

or even better

- A whiteboard and marker

Yeah, this isn’t really about tools, it can be but it doesn’t have to be.

I’m a real believer in the power of diagramming, I’m not talking about UML here. In fact I’m specifically talking about NOT UML. Boxes, lines and words are what you need. Patterns & Practices, acronyms and specific terminology can be incredibly devisive. Diagrams are a room leveller, they bring everybody into the same conversation, losing the least amount of participants along the way.

Getting Started

Think about the start of your deployment pipeline and draw the first box. Don’t go back to requirements gathering or some nonsense like that. Start with a Pull Request for example, or a merge, or in our case, joining our ship-it train.

Draw the Process

You may have a CI/CD tools that has pipelines but I guarantee there are more things involved here so draw it manually, it will free you from the constraints of the pipeline tool.

From there you want to start thinking about the stages that happen up until the point that the automation starts. There may be none if you started with a merge or there may be some human co-ordination involved.

This is key, you need to capture the human processes too.

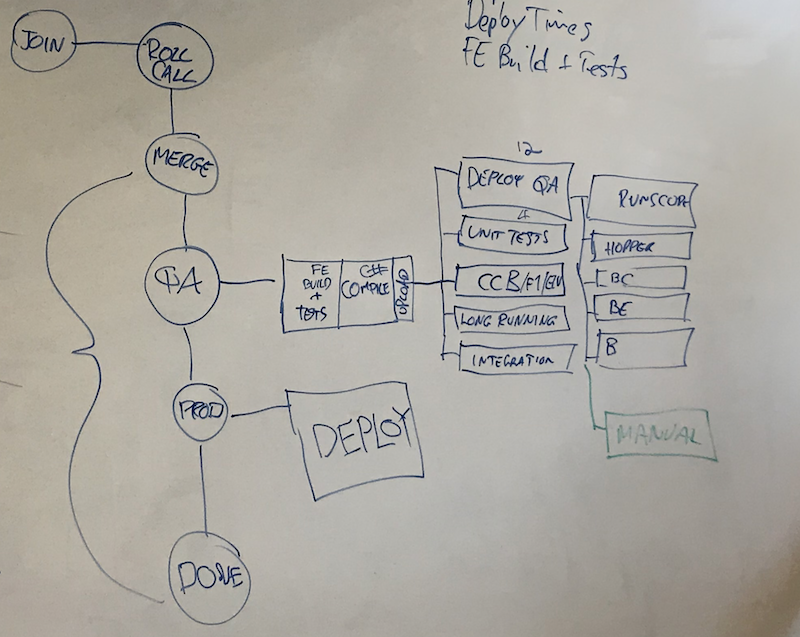

Draw each state in the state machine. Connect them with lines to show the sequence. For us this looks like

- Join

- Roll Call

- Merge

When you come to the chain of builds, draw each build stage and try to represent fan out/fan in of parallel tasks, this will become important later.

For me I choose to draw the stages as a vertical pipeline then switched to horizontal for the builds.

Your process should end with the point at which you are happy with the release in production.

Measure the Builds, Steps and Stages

The next step is to add timings to the steps involved. I find it easiest to start with the builds.

Look at your builds and test runs and take a sample of timings for each type. Figure out what the median is and write it next to that build step or test run box in your pipeline drawing.

At this point you have some timings and there are things we can infer and optimize which you will see later but resist the urge to concentrate on the automation. Often the biggest problems and most effective changes can be found elsewhere.

Note the deployment step times, for each environment. Some environments for us take longer because they have more machines.

Do the same with the manual steps and stages. In our pipeline we use a bot to orchestrate the pipeline stages, it co-ordinates the human workflow in a simple state machine by listening for prompts from engineers involved in the release. The bot posts into slack the current stage. I use the timestamp of those Slack messages to write down some timings. If you have normal human Slack conversations only, try to determine the start of each stage from the timeline or encourage folks to post the stage for a few days to get these numbers. Again take the median and add it next to each stage or step.

Note your End to End Pipeline Time

For us I like to measure from Roll Call to the start of the next pipeline. This to me is the time it takes us to ship a release.

Decide what your end-to-end pipeline measure is and take note of the time it takes. Improving this metric is your goal.

Track Why Some Releases Take Longer

Now that you have a timing for how long this normally takes, as an engineering team, start recording why it sometimes takes longer.

Some common examples are:

- Complex manual testing

- The changes touched a lot of things so it needed more manual testing

- Re-work in the pipeline

- Compile errors

- Test failures

- Reverts

- People orchestration

- Key people were in meetings, out to lunch

- I didn’t notice that I was up / required to do something

- A failed build wasn’t noticed until some time later

- A key person e.g. tester had too many things to do

Parallelize

Look at your build steps and test suites with their timings. You can now see some optimizations where parallelism can be a deciding factor in what you do next.

Can you run some things in parallel?

Some steps can be easily parallelized. If you have 5 consecutive test runs, can you do them in parallel? Your CI tool can most likely orchestrate this for you.

We chose to run some of our tests in parallel with the deploy to our test environment. Eventually we even ran our unit tests in parallel with our deploy to test. We made this decision because we looked at the failure rate of unit tests. They didn’t fail. They had already been run and passed on the developer’s machine and then again on the Pull Request branches before merge so we knew they were good. Sure, a merge could create a problem but this was so rare it was worth the risk of re-work in the pipeline.

Split Builds

Look at the longest test suites. Can they be split into multiple parallel build steps / test runs?

Don’t Spend Time Making Small Things Faster

Look at the timings. If Test Suite A takes 5 mins and Test Suite B runs in parallel and takes 10 minutes, don’t spend time on Test Suite A trying to make it faster, it won’t affect your end-to-end timings.

Look for Human Wait Times

Sure, sometimes we are waiting on the computers to do build things or test things. Often, however, it is the co-ordination of the meat-bags (humans) that is the problem.

For example, we use a build bot modelled on the Etsy train but implemented in Slack. We call it C3-PR (PR for Pull Requsts). One thing we found is that if we mention the people in the carriage we have a better chance of having them perform the tasks we need them to like Merge, Deploy etc. If you have no human involvement in your pipeline then I commend you, but most folks I talk to have some human involvement at least in failure scenarios. These human factors therefore can be very important in realising maximum throughput in your pipeline.

Be Kind To Your People

- Can your build tool notify people earlier that a test has failed and continue on with the rest or does it have to wait until the end of the test suite?

- Could an Engineer have found the source of re-work (build / test failure) earlier on their machine or the Pull Request before it was merged into master? In other words Help your engineers solve their own problems earlier, before they become everyone else’s problem

Conclusion

Hopefully this framework can help you optimize your own CI/CD pipelines. It has certainly helped me over the years when reasoning about where to spend time and why.