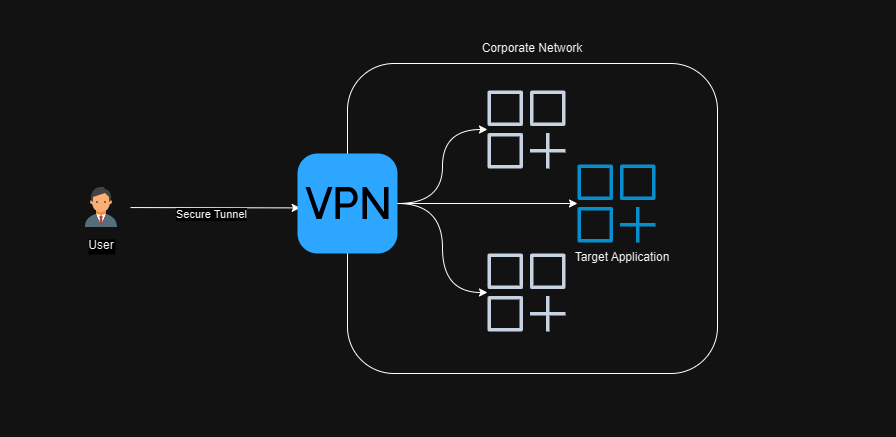

Traditional VPNs have been the goto solution for many companies when considering how best to secure access to their internal tools on the public internet. With the widespread adoption of the hybrid office and remote working in the covid era the use of VPNs has significantly increased.

Y U NO VPN?

However the traditional VPN approach has come under scrutiny in recent years due to a number of fundamental flaws in their design and implementation.

TunnelCrack and other vulnerabilities

In August of 2023 a vulnerability present in most VPNs was uncovered which could allow an attacker to convince a VPN client that a secured site behind the VPN was actually a local resource. Once in place the attacker could essentially steal any data that was intended for the target. This vulnerability was coined “TunnelCrack” and serves to represent one of the main flaws of the typical VPN architecture as we’ll see later - that not all networks should be treated the same.

If you visit the CVE databases you will also find endless disclosures of vulnerabilities in just about any VPN implementation out there. Unpatched, one of these could become an existential threat for any network architecture.

Network level access

Typically VPNs give you access to a network, or part of that network. They essentially route all traffic bound for a certain subnet or significant range of IP addresses over the VPN. This has an unfortunate side effect that the type of traffic is unbounded. Often though, we know that the individual applications we want to expose over the VPN have a single type of traffic, like simple web applications that use https, and we don’t need the rest of the network to be exposed.

It’s like the difference between allowing someone to make a phone call to a person in your organisation through your switch board vs driving the caller in an armoured car to your office door, then letting them loose inside.

Now your particular network topology likely has a way to limit these impacts. If you are using AWS for example, you can minimise this by implementing security groups, cross-referencing security groups to allow fine grained network level access but this can be difficult to manage and can become impossible at scale due to inherent limits in the number of rules you can define.

The local network becomes inherently “trusted”

When we take this border-focused approach to our network topolgy there’s a really interesting side effect that we see. This design drives us down a path where we treat anything “inside” the network in which our applications reside as “trusted”. Once inside that network there is little to stop you moving around. Hence compromising a VPN connection can lead to very dire consequences.

What if we were to assume that no networks are inherently “safe”. Well, this is where Zero-Trust comes in.

Aside: Why not YOLO your apps on the public web?

Before we tackle zero-trust we need to answer this question. It might seem like a good idea to put your applications on the public web, I mean they all can implement authentication, right?

Well, here’s the thing: I don’t trust anybody to secure the entire surface area of their web application.

What do I mean by that? Well, let’s take an example - you have a build server of some sort, maybe it’s Jenkins, that has it’s own login page so you put it on the public web. Now we all know that it needs to implement good brute force defence, well thought out password reset flows etc so maybe we choose the SAML or OIDC option that it implements so we can defer all that stuff to our Enterprise IdP like Okta. Problem solved, right? Now Okta takes care of all of our authentication concerns, right? Right?

Well, what about all those other endpoints and pages on that app - have they remembered to implement authentication on all of those and make sure none of them are exposing unauthenticated functionality or other vulnerabilities? What about in the next update, with the next feature, and the one after that?

Incidentally, choose OIDC over SAML if you can. There are many flawed SAML implementations out there and OIDC is more performance-friendly and easier to implement.

Zero-Trust

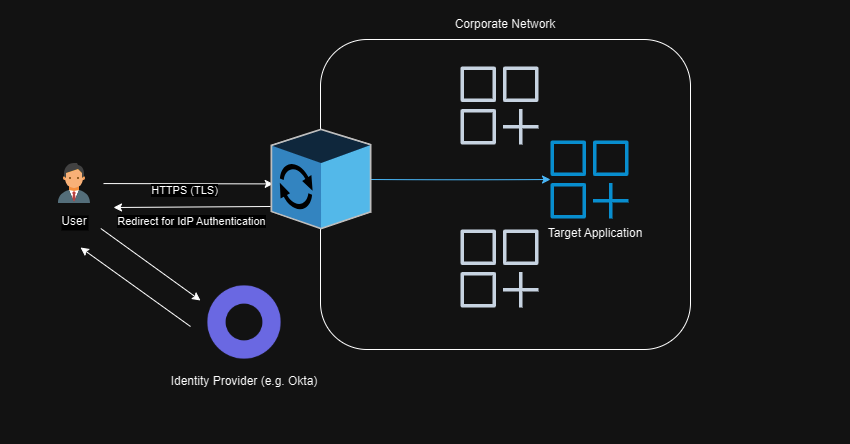

I first came across the term Zero Trust when Google published the BeyondCorp set of guidance. The major aha moment for me was the idea that, no matter if you were in a Google building or working remotely, your access to applications necessary to do your job was via the same set of controls. The major feature of those controls was an “Access Proxy”, sometimes called an “Identity-Aware Proxy”.

The idea of this proxy is that it acts as a gateway so no traffic gets through to the target app unless it has been authenticated. There’s one implementation with a very small surface area.

When I first started playing with Zero Trust I was using oauth2-proxy. It was fine but I had to run it myself on an EC2 instance, make sure it was the latest version and generally feed it myself.

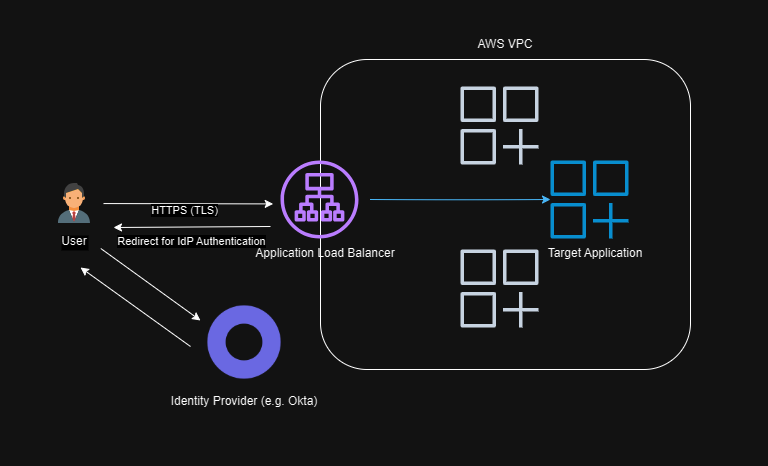

Zero Trust Access Proxies in AWS

In AWS we typically host our applications behind an Application Load Balancer (ALB). This allows us to choose to run the application in a container or on an EC2 instance while at the same time scaling it out and offloading TLS and other concerns.

A feature of the listener rules within an ALB are that you can specify that no traffic is allowed through unless the client has been authenticated via OIDC or Amazon Cognito (which in turn can support social login, SAML etc).

In this way, no traffic is allowed past the ALB unauthenticated. You can even pass through the access token, identity and claims as headers to the target application once authenticated.

A great benefit of this approach is that now AWS is responsible for patching and guaranteeing the safety of this approach and scaling the hardware. In compliance terms you’ve moved more things into their side of the responsibility matrix.

AWS Verified Access

A newer service from AWS that abstracts all of the ALB configuration away so that you can deploy a private ALB and still proxy authenticated traffic through to your applications is AWS Verified Access.

This effectively allows you to do the same thing but you don’t have to configure OIDC on each load balancer and instead can centrally configure that once. You can also use Cedar policies and device claims like MDM certificates to further implement your Zero Trust posture. The only downside here for me is the cost. AVA will cost at least US$200 / month / application whereas an ALB is only US$23 or so, depending on configuration and usage.

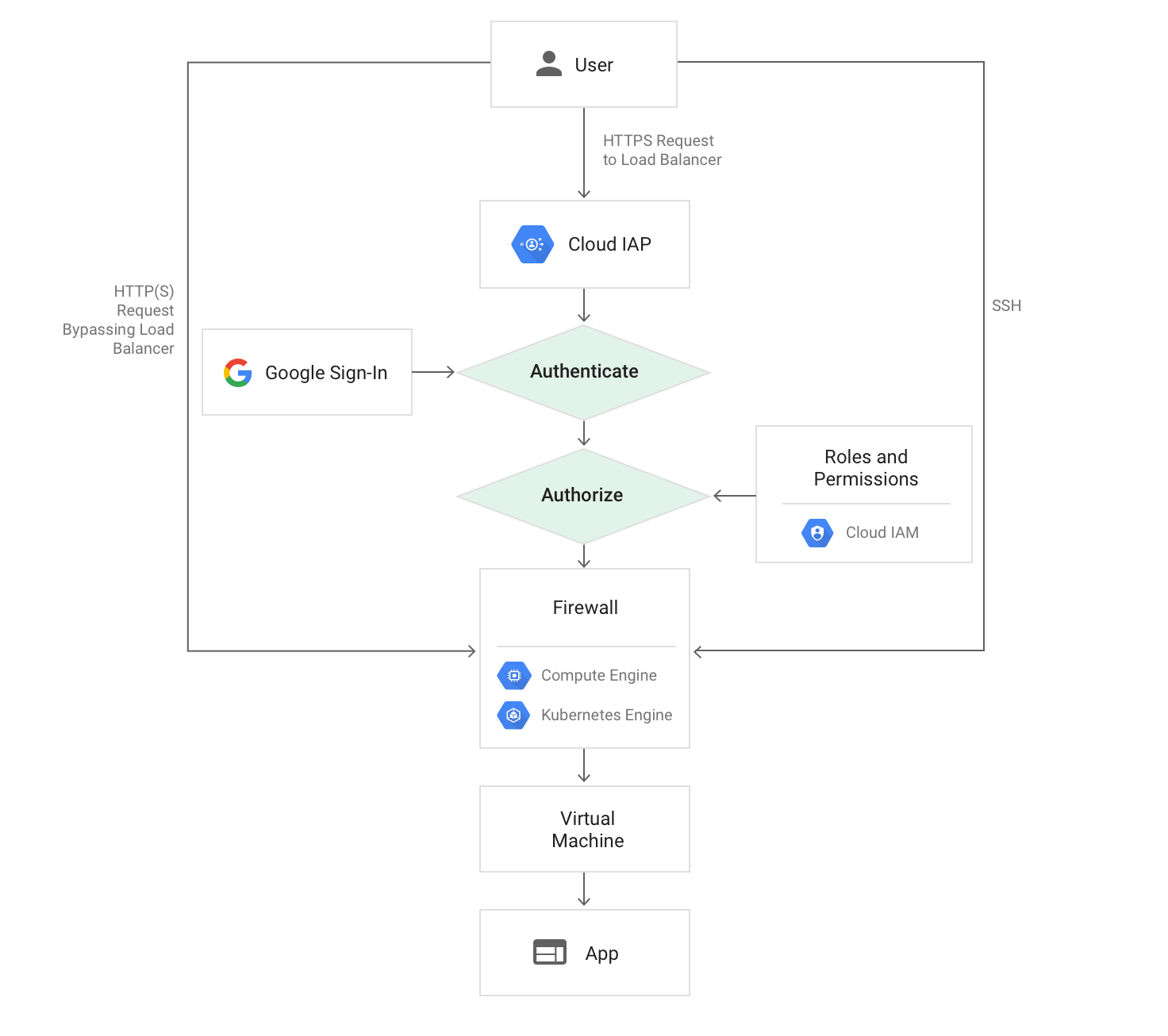

Zero Trust Access Proxies in GCP

In GCP you can implement something very similar using Google’s Identity Aware Proxy service.

Zero Trust Access Proxies in Azure

In Azure the closest thing is (I think) Azure AD App Proxy, although I’m not as familiar with this.

Summary

So really, if all you need to do is safely secure some web-based applications like your CI/CD tools, reporting, and other internal tooling but keep them accessible over the public internet then you’re better off dropping the VPN and implementing a Zero-Trust Access Proxy / Authenticating Reverse Proxy. It’s likely cheaper and safer in the long run.